He Wā Hou no ka Hale Waiū o Waiheʻe: A New Era For the Waiheʻe Dairy

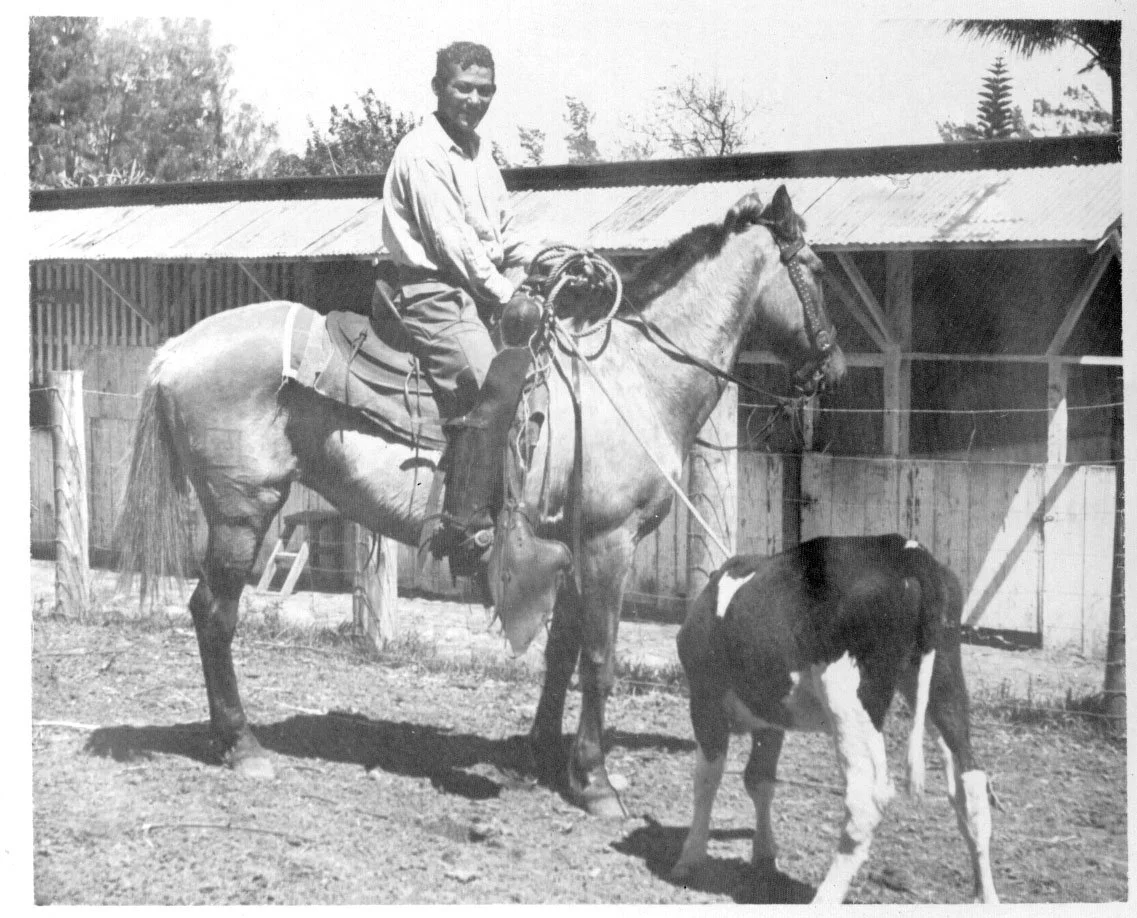

Roping calves at Waiheʻe.

As the sun set over the Waiheʻe Dairy on its last day of its operation, August 21st, 1970, once again the wahi pana of Waiheʻe faced an uncertain future. Like many sugar plantations across Hawaiʻi, the dairy’s parent corporation, Wailuku Sugar Company, struggled to remain solvent. As Maui’s economy transitioned from an island dominated by the agricultural industry toward the near complete dominance of the visitor industry, many people wondered what would become of the lands of Kapoho and Kapokea.

Many of the dairy workers were integrated into the operations of Wailuku Sugar, in most cases relatively easily. Although a number of them pointed out to me that they longed for the days on the dairy, with the tight-knit community and the work with the cattle. Over time, the equipment and buildings that were key to the dairy’s operation were swallowed by the Guinea grass, the koa haole and the kiawe.

If you push back the grasses in certain areas, you will find the large cutters that sliced the pineapple tops for the cattle feed. Looking a little closer you will see the deep pits, lined with rocks where this forage was stored. Nearby is the old slaughterhouse, built in the early 1930s after a modern and efficient design patterned after a design from Arkansas.

Although the dairy was no longer in operation, people still visited the beaches of Waihe’e, and, where it was practical, walked the coastline. Although I don’t remember it, I made my first visit to Waihe’e at the age of 4 months, during a family trip on New Year’s day, 1971. Waiheʻe was a popular place to catch heʻe (tako, or octopus) and ula (lobster), and my father, with my mother tagging along, brought me and my two brothers to Waiheʻe to replenish our refrigerator. Many people who grew up on Maui have similar stories.

My earliest memories of Waiheʻe date to a few years later, when my friend’s grandfather would load us up in his truck (begrudgingly, I’m sure) in order to teach us how to catch he’e with the pahu aniani, or glass bottom box. This device, which I only rarely see today is much as its name suggests, a wooden box with two hand grips, and a glass panel on the bottom fixed with (usually copious amounts of) caulking, through which one would walk around, peering into the puka in the coral reef. A sharp-eyed fisher could quickly spot the he’e moving over the reef, and the chase would be on. I, however, had neither the natural talent, sharp eyes or skill necessary for such activities, and no he’e were harmed in the process of me learning how to use the pahu aniani.

For nearly the entire decade of the 1970s the former dairy site lay fallow, although the former sugar cane growing areas, what we refer to as Field 9, between Waiheʻe town and the entrance to the refuge, continued to be cultivated until the mid-1980s. The homes that were not removed when the dairy closed were still accessed by Wailuku Sugar Company employees, and their families, and people held graduation and wedding parties that are still talked about today. One in particular, a Baldwin High School graduation celebration in either 1978 or 1979 (sources vary on the exact date) was apparently epic. Most often, attendees just smile, laugh and say something vague about it being a memorable party. Perhaps the details should remain known only to the past attendees.

The decade of relatively quiet tranquility came to an end with a proposal that surfaced around late 1983. Starting shortly after the end of the Second World War, the US Military decided that the atolls of the Marshall Islands would become the primary testing areas for its developing nuclear weapons system. The Marshall Islands, formerly a Japanese mandate territory given to them by the League of Nations at the end of the First World War, and before that, one of Germany’s Pacific colonies, experienced intense fighting during the island-hopping campaign in the central Pacific.

Now, to add insult to injury, two of the 29 atolls had been designated for extensive nuclear testing. These atolls are known as Bikini (famous now because, due to the nuclear testing, its name is now, cynically, associated with the swimsuit style said to resemble the islands in the atoll), and Enewetok. The first step in the process of implementing this testing program involved removing the residents of Bikini from their ancestral homeland, where archaeological evidence suggests that they had lived for approximately 3,300 years.

Bikini Islanders departing from their homes.

When asked why the military needed to, effectively, make their homeland permanently uninhabitable, the US Navy public affairs officer stated simply that these tests were necessary to ensure world peace. With nowhere to turn for any sort of justice, the 167 residents of Bikini complied and left their homeland. From 1946 on the US Military moved the former residents of Bikini from one location to another, first to an island east of Bikini, Rongerak, then to one of the islands in Kwajalein, none of which were suitable, either in resources or to preserve their culture.

By the early 1980s, the site of the former Waiheʻe Dairy, Kapoho and Kapokea, became a site considered for relocation. The exact process of how Waiheʻe was selected seems to have been lost to time, but Maui’s Mayor at the time, Hannibal Tavares, seemed to support the idea of Waiheʻe as the final destination for these ʻnuclear nomads.’ The residents of Waiheʻe thought otherwise.

A formal meeting in July of 1984 between Mayor Tavares, the lawyer for the Bikini Islanders, Mr. Jonathan Weisgall, and the President of the Waiheʻe Community Association, Mr. Milton Laʻi, provided some understanding, but the Waiheʻe residents remained skeptical. Five months later, in December of 1984, at a public hearing in Wailuku, the Maui News reported that the residents of Waiheʻe “seemed unanimously opposed” to the relocation of the Bikini residents to Waihe’e. In talking to Waiheʻe residents who remembered this chapter in their history, their opposition was not the result of animosity towards the people of Bikini, but rather at their fear that the US government would simply walk away, wash their hands of the entire situation, and absolve themselves of the kūleana they had to the people of Bikini and the Marshall Islands. In fact, the Maui News article notes that the Waiheʻe residents who provided testimony expressed sympathy for the people of Bikini. In the early days of the land trust’s presence in Waiheʻe, over twenty years after the fact, this sad chapter in Waiheʻeʻs past frequently came up.

Although the Bikini Islanders did not come to Waiheʻe, a new plan was developing. In 1985, The Maui Farm, a residential facility teaching agriculture to at-risk young people on Maui began operating there. Over the years, people have come to Waiheʻe and have told me about their experiences with The Maui Farm when it was at Waiheʻe, but these have been relatively few and far between. We have been told that both the Dairy Manager’s house (near the old Dairy facility, adjacent to our base yard) was used, and that the front porch became a pigeon coop, while the C.W. Dickey house housed a number of young people. Beyond that, we know relatively little, but if anyone reading this would like to share their story, we would welcome the opportunity to talk further.

If you have been to the Waiheʻe river mouth, or if you have walked the Refuge during the early morning hours, you may have noticed the flocks of pigeons. Although we can’t be certain of their genealogy, their presence on the refuge likely dates to the time of The Maui Farm. Ultimately, Maui Farm’s presence at Waiheʻe was relatively short-lived, as a change in ownership forced them to leave Waiheʻe.

In mid-1987 a Japanese destination golf course company, Sokan, approached C. Brewer and Company, the owners of Wailuku Sugar Company expressing interest in purchasing the Waiheʻe Dairy property. Sokan’s vision included making the site the home of a private, members only golf course, catering to the Japanese clientele. While these preliminary negotiations were taking place, a professor from the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. proposed a community archeology project at Waiheʻe.

Professor Clark leading students in support of his field research at Waiheʻe in 1987

Professor Clark, whose wife at the time was originally from Waiheʻe, believed that Waihe’e was likely one of the earliest inhabited areas of Maui. With this in mind, Professor Clark set out to do high quality archeological research, while inviting the public, especially local schools, to participate in this project. Overall, Professor Clark’s project was a tremendous success, with hundreds of students visiting the project in April and May of 1987. Among the most significant finds, however, was the discovery of a house site that dated to the 10th century (see earlier editions of this blog for a more comprehensive discussion of this finding), setting Waiheʻe as the site of one of Maui’s earliest habitations.

As the field season of 1987 ended, Professor Clark made plans to return to continue his important work. As fate would have it, the sale of the property in 1988 to Sokan put an end to the possibility of a second field season. With Sokan’s purchase of Kapoho and Kapokea, the old Waihe’e Dairy, this wahi pana was set on a new trajectory, that of a destination golf course.

However, doing so first required the completion of a comprehensive Archaeological Inventory Survey, one that would both build upon, and significantly expand our awareness of the cultural significance of Waiheʻe. This growing understanding of the historical, cultural, and ecological significance of Waiheʻe would have profound significance for the future of Waiheʻe.